|

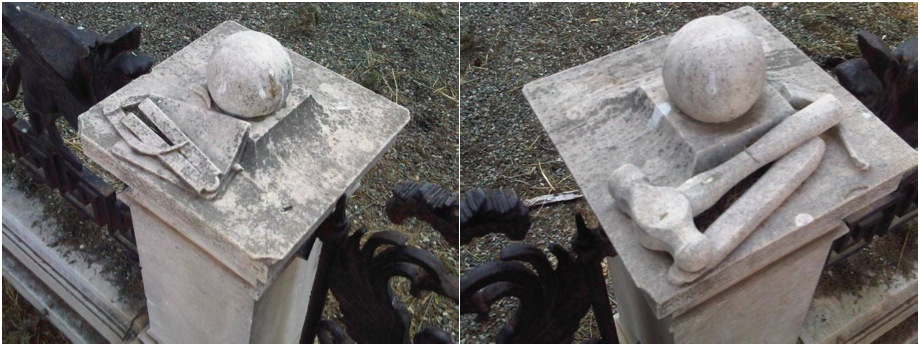

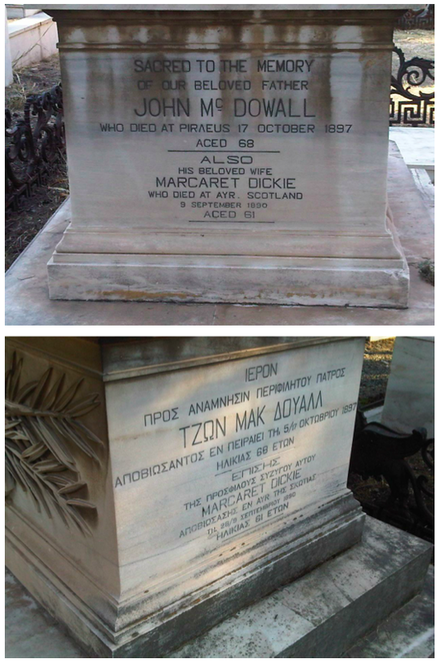

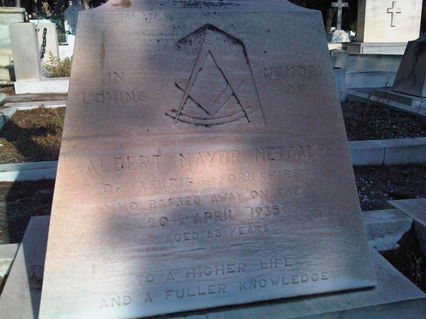

11/26/2016 0 Comments Eternal Masons RevisitedIn my stack of dead letters from Greece, only a few are in English. (A dead letter is a letter that cannot be delivered to the address written on it and cannot be returned to the person who sent it.) In the Greek Masonic Bulletin Pythagoras, issue 9 of 2002, I discover a fascinating article under the title: Eternal Masons. The accidental discovery of a grave with masonic symbols inspired the author to search for more tombs of Greek freemasons who “wished to declare their masonic identity through eternity from their grave”, and "who beyond death are still recognized by their Brethren as a mason". On the English cemetery of the Ionian island of Cephalonia, he finds the Square and Compasses engraved on a vertical tombstone with a semi circular frontispiece: “Sacred to the Memory of John Powers Late Drum Major 80 Regiment Died 2nd October 1830 Aged 36 years”. The author quotes the poem that follows and adds that: “as a token of respect this stone was erected by his comrade Sergeants (...) probably members of the same lodge”. My accidental discovery of a similar tombstone of a soldier/musician/mason at the English Cemetery of Zakynthos, from the same era, inspired me to revisit his Eternal Masons and search for some more. He only found “one Greek who disregarded the intolerance and obscurantism of his time”, I discovered a few more, not surprisingly, mainly on the Ionian Islands. This is not an inventory, neither a travel story, told chronologically or geographically; what follows is just a tale of some tombs of Greek freemasons expressing a bond between what has been and what is still to come. Within the walls of the municipal cemetery of the port city of Piraeus, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission takes care of a separate British Naval and Consular Cemetery: twenty three graves from the First World War. The small war cemetery lies at the end of the path to left from the Central Church of the Resurrection (Anastassis). The commission, so I read on their website, also takes care of twelve graves of marines who didn’t die in the war, elsewhere in this Third Cemetery. Maybe the memorial of John Mc Dowell who died in Piraeus on 17 October 1897, sixty eight years old, is one of them. Does the image of the anchor on his grave mean that he worked for the Navy? In freemasonry, the anchor is also depicted on one of the presentations of symbols, joining the Christian symbol for hope. Does the anchor rest on the branch of a palm or an acacia? As the author of my guiding article concludes: this is definitely an exceptional Masonic monument, “perhaps unique of its kind in Europe”. It doesn’t stand the comparison with the mausoleum of Eugene Goblet d’Alviella in Court-Saint-Etienne in Belgium, but in Greece it surely doesn’t have its equal: in its context it is as explicit, as courageous and as rich. The plot is enclosed by a cast iron rail of sixty centimeters height, standing on a stone base. On a ribbon of the repetitive Greek meander design, between several marble columns, two griffins are separated by thorns. The gate to the enclosure bears two sphinxes, looking at each other, holding blossoming thorns; on top of them an owl spreads his wings. The plot is divided in two: on the neighbouring monument to the right and on the two graves at the foot of this monument no Masonic symbols occur. We are acquainted with the mythological griffins with their heads and wings of an eagle and their feline body. They decorate many balconies of neo-classical buildings in Athens: from 15 Kanari Street and the Museum of Cycladic Art in Kolonaki over the Parnassos Literary Society to commercial buildings in Plaka: Quick Pitta, John Papanicolaou Furs, some ramshackle edifices in Athina Street. And on the residence of Heinrich Schliemann, the 19th century archeologist; today his mansion houses the Numismatic Museum and still hosts griffins and even sphinxes. If these sphinxes, half women half lion in its Greek tradition, from Delphi to the rooftop of Academia, often represent spirits who dare passersby to elaborate on the meaning of life, they indeed fit better on the gate to a grave than on the windows of an urban mansion. But why elaborate on the allegory and speculate if it, in its nineteenth century neo-classical version or in its earlier Greek representation, point in the direction of freemasonry, more obvious and recognisable on this tomb are the tools, casually placed upon the columns, on both side of the gate, as on an altar, accompanied by what appear being an earth globe and a star globe. What a pity sculptures on the other columns have disappeared. On one of them, only the feet of a bird, an owl perhaps, have survived vandalism. The monument itself is a temple resting on a base probably of Pendelicon marble, with in front the sign of the anchor, on the left the identity of the grave in English and the translation of the information in Greek on the right side. The temple is carried by four Doric columns, two in the front and two in the back. The bust of the deceased stands on a round column carrying proudly the Square and Compasses, in the second degree. He wears a medal: profane or masonic? On his cap the ribbon of meanders is depicted. First Cemetery of Athens No masonic imagery appears on the grave of Heinrich Schliemann, according to many a freemason indeed. On the contrary, the memorial, megalomania in stone, looks down on all who enter the cemetery, high from above, to the left just behind the entrance. I can only honour him with the photo of a simple red rose left by an anonymous admirer. The contrast with the stone commemorating one of Greece’s sons cannot be bigger: Emmanuel Xanthos, freemason and founding member of the secret liberty movement Filiki Eteria. Instead of an ostentatious mausoleum, I stand in front of a block of raw stone, bearing a simple cross, with a braided crown and a black ribbon placed against it; a metal plate refers to masons who fought for the independence, dating from 1930. On the backside of the base his name is repeated and several years are remembered: 1872 and 1905. Is this really his grave or is it a memorial? Has he been commemorated in these years? Have his remains been brought here? Or does he still rest on Patmos where he was born? Back to the Eternal Masons mentioned in the Pythagoras Bulletin. Within the fence of the Protestant Cemetery, still in the First Cemetery of Athens, against the outer wall of the main cemetery, lie the graves of two masons, openly claiming they were members of the order. Square and Compasses decorate their simple graves. On the first one, they mark the base of the cross in a large but simple bed of gravel; on the second one, our signs stand central on the simple slab. Albert Mayor Metcalfe of Askrigg Yorkshire died on 20 April 1935, sixty three years old. “To a higher life and a fuller knowledge”, says the stone. I don’t know if this is a standing expression; what I do recognise is the masonic sense of the thought. John Hadfield, born in Royton, England, on 25 August 1900, died in Athens on 20 September 1969: "God knew you were weary and he gave you rest". Square and Compasses are embedded in some kind of a bell. Both of them, John Hadfield and Albert Mayor, were former presiding masters, weren’t they? Another grave in the First Cemetery of Athens “lies behind the Church Of St. Lazarus, to the left, and belongs to the Galatis family”, so writes my guide. And further: “observing this partly underground monument, the marble cover to the reliquary has a small carving of a shield with the Square and Compasses”. I’ve been circling the Church of Lazarus as a Muslim the Ka’aba, until we, further on the path to the Protestant Cemetery, stumble upon the name of Galatis by accident. “Bro Galatis of Hesiodos Lodge is a hero of the National Resistance, member of the strike force of the resistance organisation P.E.A.N.A. (...) This is possibly the only Greek declaring his special identity from the grave”, so I read in my guide and add: discretely but unambiguously, inside, through the metal gate to the cellar, it stands clearly carved in marble. Flash back 1, December 2011, my first trip to Zakynthos: « The Italian occupier named the island the Flower of the East, as it also houses The Star of the East, the only lodge outside England resorting directly under the Grand Lodge of London. Zante has a thing with Freemasonry.” On the Ionian Islands of Corfu, Lefkada and Zakynthos/Zante the first lodges in Greece were established. Almost a year later, I discover on the Central Cemetery the grave of “Ioannis Zarakinis: worshipful Master of the English Lodge of Zakynthos”. Above Square and Compasses, only his name and Masonic function is noted, nothing more, no dates, no thoughts. On the foot stands a simple cross, in the large bed lie a fallen pot of flowers and grows a leaf. Only a foreigner would keep on looking for signs under the midday sun in a temperatures approaching 40°; there was a time when I wouldn’t hesitate defining more graves as Masonic, today I consider the “all seeing eyes”, “the obelisks” and “five pointed stars” as welcoming fata morgana’s where I can pause to drink refreshing water. Only one more tombstone carries unmistakably the signs. And so this well kept monument of Dionysios Pilarinos gets all the attention it deserves. He was a politician and a physician: “he devoted his life to his fellow men”. Below the tombstone has the illustration of a three armed chandelier and both sides have very prominently the Square and Compasses with the G. Driven by the article in Pythagoras, I visit the English cemetery of Zakynthos. Officially, the cemetery is closed because of “instability”, but after a few insisting returns, the caretaker of the neighboring garden shows me in. Here rest mainly British service men and a few non-orthodox gentlemen and even ladies who were not welcome in the local cemetery. I also found two English consuls, the one of the Peloponnesus, who died in 1689 and initiated the first of three English cemeteries on the Island, and the one of Cephalonia and Zakynthos who died in 1728. And then there is the gravestone of Fredrick Dedrick: “late Sergeant of the Band of the 11th Regiment of British Infantry. He is born in an unreadable city in Prussia in 1789 and died here on 23 October 1834. The stone was erected by his fellows of the band. On top of the monument, just underneath Sacred to the Memory of, are, in all its simplicity, the token of masons. The Story of Freemasonry on Zakynthos would not be complete without a visit to the church of Aghios Georgis ton Filikon or Saint John of the Friends. Flashback 2, December 2011, my first trip to Zakynthos: “The spot that once hit one of the biggest secrets of Greece lies in Psiloma, just above the city, after a sharp turn in Filikon street, coming from the street named after Capodistriou. On the north side of the church, in a small garden under an olive tree, the memorial for the Friendly Society attracts all the attention. To the south, under the clock tower, is a monumental grave; I cannot read who occupies the giant bird cage. Against the western wall, a remembrance of freemasons dates from 1925." The Synagogue, the Jewish cemetery and the war memorial of Chalkida are known worldwide. Today I come to check on one of the few Masonic graves of a Greek mason, already described in Pythagoras: “It is an ancient Greek type marble column, with a capital with thorns and a cross on the top. On the top part of the column is a laurel wreath in relief and in its center are the Square and Compasses. On the lower part is the inscription: (...); translated: “to the memory of our beloved parents Constantinos Fleggas and Adamantia Eliadou. Their Children”. Unfortunately, the beautiful capital has disappeared today: stolen or removed and kept safely elsewhere? Most masonic graves in Greece are of foreigners. In a last effort, I go to places where thousands and thousands of foreigners lie side by side. On the Phaleron Commonwealth Cemetery, on the busy Poseidon Avenue, opposite bars and yacht clubs in Vouliagmeni, almost 3000 soldiers of the other side try to find rest. The architecture is as straight, its tombstones identical, bearing almost all a cross, some a Star of David, a few the Fatiha. There is one Dutchman, 600 unknown, a memorial for the cremated, mainly Indian, and for the victims of the French-British campaign in the Crim.

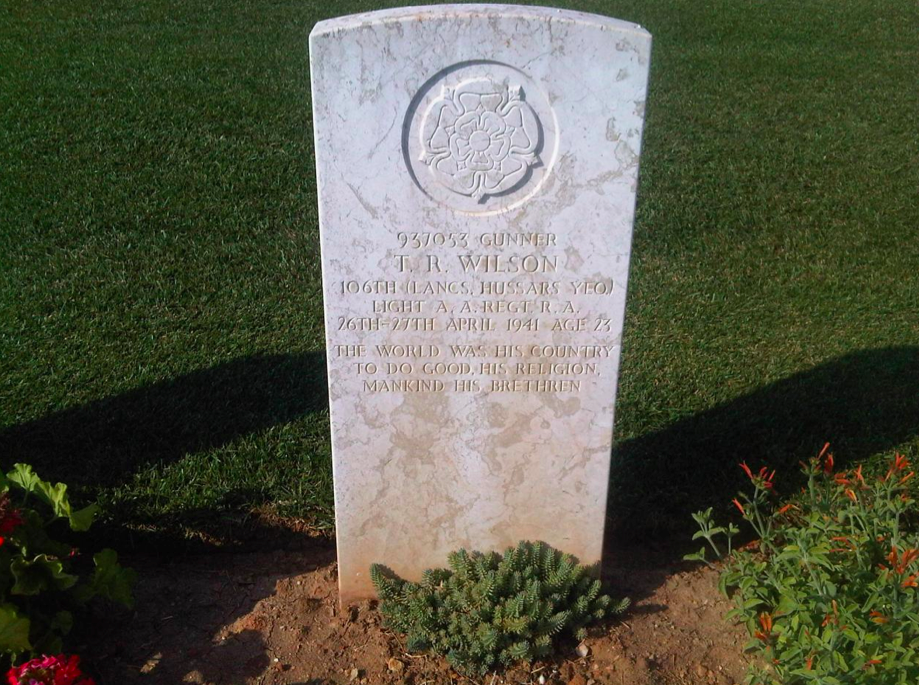

Between al this human waste, only the stone of twenty three year old T.R. Wilson catches my eye. This is one of the very few graves that do not bear a religious sign, neither an impressive coat of arms. This stone only carries a stylish flower, perhaps a Tudor Rose, and this subscription: "The World was his country to do good, his religion, mankind his brethren. The message sounds familiar to masons. Google confirms: “my country is the world and my religion is to do good”, is a well known quote of Thomas Paine from The Rights of Man, written in defense of the French Revolution in 1791-1792. Many other web sites quote the text more closely to the grave script of T.R. Wilson: “The world is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.” Apparently Paine was not always quoted correctly, even by the relatives of T. R. Wilson, who furthermore massacred the grammar. The notion of the brotherhood has probably been added by freemasons: relatives of Wilson? Or was Wilson a mason himself? We can only guess. Many doubt that even Thomas Paine was initiated. We only know he might have had some sympathy for the order. Didn’t he write: "An Essay on the Origin of Free-Masonry" (1803–1805)? Was Thomas Paine a mason or wasn’t he? Was T.R. Wilson a Brother of wasn’t he? In the end, does it matter? Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human rights clearly states: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

0 Comments

|

Posts may evolve in articles, or vice versa. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed