|

“Ze zullen hem begraven in het dal van de Vlierbeekabdij, bij de witte kerk met de bolvormige toren die vanuit Oostenrijk naar hier schijnt te zijn overgekomen.”

Met die zin doet de Vlaamse schrijfster Loekie Zvonik haar debuutroman uit 1975 toe. Als Hermine Zvonicek werd ze geboren in Gent op 17 januari 1935; ze heeft lang in mijn Limburgse dorp gewoond. Hoe heette de hoedenmaker? is een doorzichtige sleutelroman. Didier, reisgenoot van Hermine in het boek, is een auteur die door zelfmoord is geobsedeerd. Een paar maanden nadat de oude studiegenoten elkaar opnieuw hadden opgezocht en tijdens een literair congres in Wenen een affaire hadden, stapt de schrijver Dirk de Witte, op 27 december 1970, op zijn berg in Kessel-Lo bij Leuven, in zijn auto en uit het leven, uit dat van Zvonicek en uit dat van zijn vrouw, Anne Hoegaerts. Figuurlijk werd ik aan het trio voorgesteld toen ik in de vroege jaren tachtig De Laatste Deur, Zelfmoord in de Nederlandse Letteren van Jeroen Brouwers kocht. Ik heb toen dorpsgenote, lerares en schrijfster Zvonicek nog proberen te interviewen maar de witte bungalow op de heide bleef toe. Onlangs kreeg ik de nieuwe en herziene editie, de vijfde druk, van De Laatste Deur cadeau. Ook koester ik nog altijd de derde druk van Hoe heette de Hoedenmaker? Zoals bibliotheken soms kerkhoven zijn en graven boeken staat op de omslag de foto van een oude grafversiering: een kruis van emaillen witte rozen. Dirk de Witte was niet in graven geïnteresseerd, behalve misschien in dat ene in zijn geboortedorp. Toen Didier op de universiteit vertelde dat zijn wieg in Sint-Amands stond, kreeg hij, volgens Zvonik, deze reactie: “Zeer goed zei de professor en knikte, als in een zegening, alsof het wonen te Sint-Amands, aan de Schelde, iemand voorbestemde om zegeningen te ontvangen, zeer goed, en begon links en rechts te informeren wie dan wel begraven lag in het Scheldewater te Sint-Amands.” Zijn korte leven lang was Dirk de Witte niet op zoek naar graven maar naar de ideale methode om dood te gaan. Hij zocht vooral in boeken van schrijvers-zelfmoordenaars zoals Heinrich von Kleist, Cesare Pavese, Stig Dagerman. De techniek om zich efficiënt in een auto te vergassen beschreef hij in zijn laatste verhaal: hij had erover in een krant gelezen, misschien zelfs in Wenen. Ook daar dacht Didier/Dirk niet aan zijn graf maar alweer aan dat van Verhaeren: “Onderaan de heuvel ligt de Donau. Breed en kalm. Hij doet denken aan de Schelde te Sint-Amands, rust, vrede, maar ook modder en afval, en waar Emile Verhaeren begraven ligt, bijna in het water en bij springvloed klimt de stroom zeker over zijn tombe, zodat de letters verdwijnen: ‘Ceux qui vivent d’amour, vivent d’éternité’.“ Zoals de dichter Heinrich von Kleist zijn ex-geliefde Henriëtte Vogel met een dubbele zelfmoord naar een gemeenschappelijk graf aan de Wannsee bij Berlijn heeft meegenomen, zo wilde Didier zijn Hermine met zijn zelfmoordobsessie infecteren. Maar ze had hem door en keerde na Wenen naar haar leven en haar man terug. Op zijn laatste reis nam de Witte dan maar zijn hond mee. Dat hij niet zijn surrogaat Henriëtte, Hermine, had geïnfecteerd maar zijn vrouw Anne, heeft hij gemist. Zeven maanden na de zelfmoord van haar man stapte zij op 27 juli 1971 voor haar laatste reis, in zijn auto en paste dezelfde methode toe. Zij nam de kat mee. Een dubbele zelfmoord, dan toch, en in uitgesteld relais. Brouwers vindt dat men Dirk de Witte niet herinnert vanwege de literatuur die hij heeft gemaakt, maar vanwege zijn zelfmoord. Meedogenloos is hij voor de literaire erfenis van zijn vroegere vriend en rivaal-verzamelaar van zelfmoordverhalen. Sint-Amands is te klein voor twee grote schrijvers, zo maakt hij hem nog af. Maar misschien zijn we de Witte ook vergeten omdat hij niet genoeg voor de liefde had geleefd, zo schrijf ik Verhaeren nog na. De zin die als echo in het dal van de Vlierbeekabdij weerklinkt, werd eerder gelanceerd in Hoe heette de Hoedemaker? “Mooi is het daar, zegt hij. Om de kerk heen ligt een begraafplaats achter een brokkelige muur en er is een tuin met een landelijke herberg en ijzeren stoeltjes onder hoge bomen. De kerk met de bolvormige toren staat wit en geel in de schemering en de verre straatverlichting, en schijnt vanuit Oostenrijk naar hier gekomen.” Aan de ingang van het kerkhof, achter diezelfde brokkelige rode bakstenen muur, hebben Dirk de Witte en Anneke Hoegaerts, onder één steen, lang in de schaduw van een boom gelegen. Vandaag steekt alleen de afgezaagde stronk aan de rechterbovenhoek boven het graf uit. Onder de ondergaande zon weerspiegelt de toren van de voormalige abdijkerk op het zwarte marmer. Onder een simpel kruis staan alleen hun namen, elk met een dubbel jaartal. Citerend uit de afscheidsbrieven van Henriette Vogel en Heinrich von Kleist, ziet Brouwers ze daar liggen: “samen, dat wil zeggen, elk apart.” Hermine Zvonicek stierf op 17 augustus 2000 in het Sint-Salvatorsanatorium in Hasselt; ze was vijfenzestig. Haar as werd er verstrooid op de begraafplaats Kruisveld. Op 9 juni 2006 overleed haar echtgenoot; zijn as werd aan hetzelfde veld toevertrouwd. “Samen, dat wil zeggen, elk apart.” Loekie Zvonik woonde in mijn dorp; ik heb er lang tevergeefs naar haar graf gezocht.

1 Comment

7/8/2017 2 Comments Lezing 25 juni 2017Eén van de mooiere uitspraken over verjaardagen is deze: van de verjaardag van een dame herinnert een gentleman zich alleen de dag en de maand, nooit het jaar.

Dat geldt ook een beetje voor de club van gentlemen die zich Les Disciples de Salomon noemt maar die precies niet goed weet hoe oud de vrijmetselarij in Leuven is: ‘meer dan 200 jaar’, zo staat op de affiche. Die twijfel heeft niets te maken met de bekentenis dat er voor of na een logezitting al eens een glaasje wordt gedronken, soms zelfs één teveel zoals straks zal blijken, want de dag en de maand herinneren we ons altijd. Op vierentwintig juni vieren we de geboorte van de heilige Johannes, Johannes De Doper, Sint Jan. Dat gebeurt elk jaar, samen met vele andere maçonnieke werkplaatsen die, niet toevallig, “loges van Sint Jan” worden genoemd. Die traditie is overgenomen van oude Engelse loges die Johannes de Doper als patroonheilige hadden. Daarom is het ook niet verwonderlijk dat vier van die loges, op 24 juni 1717, zich in de Londense taverne The Goose and the Gridiron verenigden in de Grand Lodge of London and Westminster, voorloper van het overkoepelend orgaan the United Grand Lodge of England dat tot vandaag toekijkt op het naleven van de maçonnieke traditie, de regulariteit om het met een wat meer geladen woord te zeggen. Niet alle vrijmetselaren volgen de traditie immers even strikt. Maar regulier of irregulier, dogmatisch of a-dogmatisch, algemeen wordt 24 juni 1717 beschouwd als een historische dag, volgens sommigen veeleer een symbolische datum, in de geschiedenis van de speculatieve vrijmetselarij; speculatief staat tegenover operatief zoals, bijvoorbeeld, de steenhouwersgilden die veel verder teruggaan. Zoals Engelse loges Johannes de Doper herdachten, zo vierden de eerste Schotse loges die andere Sint Jan, Johannes de Evangelist. Zo komt het dat de meeste loges tegenwoordig de twee feesten van Sint-Jan vieren: dat van de Doper, op de dag van de zomerzonnewende, de dag waarop de zon in het zenith staat, het moment waarop de dag het langst is en de nacht het kortst, en dat van de Evangelist, op de dag van winterzonnewende, het moment waarop de dag het kortst is en de nacht het langst. Niet alleen de christelijke traditie kijkt naar de solstitia, ook andere religies. Er is zelfs een niet-christelijke voorganger, de Romeinse god met de twee gezichten, Janus Bifrons: op de dag van de winterzonnewende opende hij de poort van de hemel, want er komt meer licht aan: Jantje lacht; op de dag van de zomerzonnewende opende hij de poort van de hel want het wordt weer donker: Jantje weent. Om vandaag de zegen van de UGLE te krijgen, moeten vrijmetselaren werken ter ere van de Opperbouwmeester van het Heelal (al moet dat begrip verder niet worden gedefinieerd), wordt de opname, de initiatie, alleen voor mannen, bevestigd op de bijbel, de passer en de winkelhaak (of een ander, zogenaamd Boek van de Heilige Wet) en wordt in loges niet over politiek of godsdienst gesproken. Niet alle vrijmetselaren kunnen zich daarin vinden en dat zorgt al decennia voor spanningen, afscheuringen en een schisma, zeker op het Europese continent en in België. In de beginjaren werd het probleem lang niet zo scherp gesteld. In ons land zijn de verschillende visies van min of meer respect voor de traditie pas na onafhankelijkheid de geschiedenis van de vrijmetselarij gaan bepalen. Op 21 oktober 1854 besliste het toenmalige overkoepelende orgaan, het Grootoosten van België, om het verbod op politieke of religieuze debatten, te schrappen, en in 1870 verdween ook de verwijzing naar een opperwezen. Dat viel niet goed bij degenen die wel over het kanaal keken, maar, ondanks inspanningen om Engeland te vermurwen, verloor de Belgische maçonnerie haar aansluiting bij de universele vrijmetselarij. Daarna legden twee bijzonder traumatische wereldoorlogen de vrijmetselarij bijna helemaal lam, maar bij de heropleving in de jaren vijftig groeide ook het verlangen om terug te keren naar oorspronkelijke vrijmetselarij. In 1954 hadden belangrijke Europese grootloges in Luxemburg al een dergelijke intentie in een conventie uitgesproken, maar het Grand Orient de France en daarin gevolgd door een meerderheid van het Grootoosten van België, wilde niet volgen. Dat leidde in 1959 in ons land tot de oprichting van een tweede overkoepelend orgaan: de Grootloge van België splitste zich af van het Grootoosten van België. Tot de initiatiefnemers behoorde een Franstalige loge uit Leuven: La Constance. In de daaropvolgende jaren werden ettelijke nieuwe reguliere werkplaatsen gesticht en in de dynamiek werd in deze stad ook de Nederlandstalige: Les Disciples de Salomon opgericht. Dat gebeurde op 24 juni 1967. We vieren dus niet alleen de driehonderdste verjaardag van de eerste Engelse Grootloge, of een begin van de speculatieve vrijmetselarij, wij vieren ook dat onze loge precies vijftig wordt. Nochtans komen in documenten die ouder zijn dan 1967 al verwijzingen naar Les Disciples de Salomon voor. Ik nodig u uit naar de Franse Tijd. Na de overwinning van de Fransen op het Oostenrijkse keizerrijk werden de Zuidelijke Nederlanden vanaf 1794 door Franse troepen bezet. Daarmee brak een bloeiende periode aan, toch voor de vrijmetselarij. Overal werden toen, vooral door Franse militairen, loges opgericht, eerst in Brussel, daarna elders, ook in Leuven. We zijn daarover vrij goed geïnformeerd dankzij een uitvoerig reisverslag van Pierre Nicolas Riffé de Cambray, die in 1802, in opdracht van het Grand Orient de France, het maçonnieke landschap in onze contreien bestudeerde. In zijn verslag vermeldde de Cambray onder meer zijn ontmoeting met leden van de Leuvense loge Les Disciples de Salomon, “zopas opgericht (in 1801) en die hun erkenning door het Grand Orient de France hebben aangevraagd”. In Parijs worden tot vandaag drie documenten bewaard, gedateerd op 21 juli 1801, met o.m. de lijst van de acht Belgische stichtende leden van Les Disciples de Salomon. Op 28 januari 1802 vermeldt een tweede lijst al dertig leden, waaronder 14 Fransen van het militair hospitaal, le Succursale de l'Hôtel Impérial des Militaires Invalides. In 1802 vernoemt Riffé de Cambray o.m. de Commandant van het hospitaal, Generaal Jacques Pierre Varin als één van de leden. De eerste samenkomst had plaats op 18 maart 1802. De formele installatie van de loge had twee jaar later plaats en ook daarvan bestaat nog een volledig verslag. De feestelijke dag begon aan de poorten van de stad, waar een delegatie van Les Disciples de Salomon bezoekers van de Brusselse loge Les Vrais Amis de l’Union verwelkomde. Onder ruime belangstelling van de bevolking werd het gezelschap in koetsen naar het lokaal van de Société littéraire gevoerd, waar “een sobere” maaltijd werd genomen. Zoals dat vandaag nog gebruikelijk is, beschrijft de secretaris daarna gedetailleerd de consecratie van de Achtbare Sint Jansloge, Les Disciples de Salomon, op 18 maart 1804. Les Disciples de Salomon groeide uit tot een bloeiende loge, met als leden de burgemeesters uit die tijd, professoren, de omgeving van de familie Artois, priesters ook. In 1807 bereikte de loge het maximum aantal leden dat de statuten toestond: negentig. Niet zonder moeilijkheden richtte de voorzittend meester van Les Disciples de Salomon, Louis Paulin Chillâtre, een nieuwe loge op die hij de naam gaf van zijn Parijse moederloge, La Constance. Ze wordt geconsacreerd op 28 augustus 1808. Les Disciples de Salomon was zeker nog actief tot in de periode van het Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden. Ook voor de vrijmetselarij was die vereniging vanaf 1814 niet gemakkelijk. Omwille van de taal maar ook wegens het verschil in mentaliteit was in het Zuiden de verlatingsangst van het Grand Orient de France groot. Koning Willem I had zijn jongste zoon, Prins Frederik, benoemd tot grootmeester van het Verenigd Koninkrijk met als opdracht Noord en Zuid ook maçonniek te verenigen maar dat was geen gemakkelijke opdracht. Les Disciples de Salomon kreeg nog wel het bezoek van Prins Frederik en zijn oudere broer, kroonprins en daarna Koning Willem II, maar de omwenteling van 1830 zorgde ook alweer voor een maçonnieke ommekeer. Uitgerekend op 21 juli 1831 moest Les Disciples de Salomon verhuizen en ze zou die crisis amper overleven. Bij de oprichting van een onafhankelijk Grootoosten van België, op 23 februari 1832, was wel La Constance betrokken maar niet meer Les Disciples de Salomon. Ze was toen al op sterven na dood; rond 1839 doofde ze uit; sommige van de leden gingen over naar La Constance. Les Disciples de Salomon is dus ouder dan de vijftig die ze sinds haar heroprichting van 1967 is geworden. Gesticht in 1801, onder diezelfde naam, heeft ze al 216 jaar haar plaats in het Leuvense maçonnieke stadslandschap. Misschien al wel langer, en daarvoor nodig ik u uit naar Oostenrijkse periode die de Franse voorafging. Tussen 1715 en 1794/95 werden de Zuidelijke Nederlanden bestuurd door de Oostenrijkse tak van het huis van Habsburg. De eerste loge in onze contreien zou dateren van 1721, opgericht in Bergen, gevolgd in 1730 door nog een paar werkplaatsen maar veel bewijzen hebben we daar niet van. Documenten zeggen wel dat in 1743 in Brussel twee loges werden gesloten. Een centrale figuur in die periode was Markies François-Bonaventure Joseph du Mont de Gages. Hij is in Leuven aan rechten begonnen maar dankzij zijn snelle opgang als rijke edelman heeft hij zijn studies afgebroken en is al gauw een “professionele maçon” geworden. Via Franse contacten werd hij eerst benoemd tot ‘Provinciaal grootmeester in de Oostenrijkse Nederlanden’, maar later sloeg hij zijn bewind om naar het Engelse model en zag hij, als vertegenwoordiger van de Engelse grootloge, toe op de stichting van tientallen loges en hun erkenning in de regulariteit van Engeland. Een voorbeeld daarvan is de studentenloge La Parfaite Amitié, Zur Vollkommenen Freundschaft, volgens sommigen in Leuven actief in de jaren 1766-1772. Omdat de interesse hier achteruit ging, verhuisde de loge naar Brussel waar ze in 1772 een constitutiebrief van markies de Gage kreeg. Vrij snel na die verhuis, in 1773, zag echter een nieuwe loge in Leuven het licht. De naam is niet bewaard gebleven en ze werd evenmin erkend door de Provinciale Grootloge maar van haar reputatie zouden we daarna nog horen. Onder de stichtende leden waren studenten van de faculteit rechten; ze kwamen samen in een herberg en daar is het op een dag fout gelopen. Begin 1774 werden de overheden gealarmeerd door ‘herrie en heibel’ die in deze studentenloge de ernstige vrijmetselaarsarbeid had verstoord. Na afloop van een zitting, en een waarschijnlijk overvloedig overgoten broedermaal, vielen de studenten de waardin lastig en kregen het letterlijk aan de stok met de waard. Tegen de ochtend verstoorden ze zelfs de aankomst van gasten in de herberg, o.m. de echtgenote van Graaf Nicolas Antoine d’Arberg die net had ingecheckt. De Graaf was niet minder dan de plaatsvervangende grootmeester van de Provinciale Grootloge. Het hek was van de dam. De Leuvense academische overheid werd op de hoogte gebracht en het schandaal bereikte zelfs de landelijke politiek, t.e.m. landvoogd Karel van Lotharingen en keizerin Maria-Theresia. Studenten mochten niet meer aan maçonnieke zittingen deelnemen. In 1776 werd de vrijmetselarij zelfs voor enige tijd geschorst. Na de dood van keizerin Maria-Theresia in 1780, kwam zoon Jozef II op de troon. In een golf van hervormingen, pakte hij vijf jaar later ook de vrijmetselarij als broeinesten van protest aan, maar in 1789 brak de Brabantse Revolutie uit en werden de Oostenrijkers verdreven. Ondanks een kort Belgisch intermezzo, zou het nog tot minstens de eeuwwisseling duren vooraleer het wat rustiger werd en ook de maçonnieke activiteiten weer hervatten. We zagen eerder al dat La Constance in 1808 werd opgericht en Les Disciples de Salomon in 1801. Bij de plechtige oprichting in 1803 herinnerde één van de stichters van Les Disciples dat hij 30 jaar eerder al aan de wieg van een Leuvense studentenloge had gestaan. En in een brief verwees een ander dat hij met genoegen terugdacht aan zijn oude loge, meer dan 32 jaar geleden. Het staat er niet zwart op wit maar Les Disciples de Salomon zou wel eens de voortzetting kunnen zijn van die oude verboden studentenloge; de vrijmetselarij in Leuven is in ieder geval bijna 250 jaar oud. U herinnert zich dat Les Disciples de Salomon uitdoofde in 1839. Ook La Constance had eerder al een crisis doorgemaakt, bij het uiteenvallen het Franse keizerrijk, maar in 1818 werd ze heropgericht. Sindsdien heeft La Constance haar vele omzwervingen in de stad goed overleefd, tot ze in het begin van de twintigste eeuw haar stek vond op het terrein Gasstraat (nu de J.P. Minckelersstraat) waar vandaag nog het logegebouw van Leuven ligt. Tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog heeft het veel schade geleden; tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog kregen La Constance en de loge het nog zwaarder te verduren. Het gebouw van de loge werd geplunderd door de nazi-bezetter, en op 1 maart 1942 kwam een rondtrekkende anti-maçonnieke tentoonstelling naar Leuven. Een voormalige achtbare meester werd naar Breendonk gedeporteerd en afgevoerd naar Buchenwald. Andere broeders kregen doodsbedreigingen en anonieme brieven. Jean Naveau werd vermoord. Maar zoals de mythische feniks altijd opnieuw uit zijn eigen as wordt geboren, en in 1808 uit de oorspronkelijke loge van Les Disciples de Salomon, La Constance voortkwam, zo werd, vijftig jaar geleden, op 24 juni 1967, precies vijftig jaar geleden, in de schoot van La Constance, Les Disciples de Salomon heropgericht. Het belangrijkste motief van dertien broeders van La Constance was om in het Nederlands te werken, maar ook aansluiting bij de eigen volksaard te vinden. Zoals in vele toenmalige Belgische loges werd in La Constance sinds haar oprichting in 1808 de vrijmetselarij immers in het Frans beoefend. Die jaren zestig waren ook voor de universiteit erg woelig. Studentenprotest (Leuven Vlaams, Walen buiten) sinds 1966 leidde in 1968 tot de val van de regering, tot de splitsing van de universiteit en de oprichting van l’UCL in Louvain-la-Neuve bij Ottignies. Voor alle duidelijkheid, zowel La Constance als haar Vlaamse dochter die tegelijk haar moeder was, Les Disciples de Salomon, ressorteerden toen onder de Grootloge van België, sinds haar oprichting in 1959 nog erkend door de United Grand Lodge of England. But old habits die hard. Velen in de Grootloge respecteerden een aantal universele principes niet, zoals het niet-toelaten van irreguliere bezoekers. Ook het opperwezen werd weer in vraag gesteld. In 1979 viel de Grootloge van België in Engeland in ongenade. Zoals twintig jaar eerder de Leuvense loge La Constance aan de wieg stond van de Grootloge van België, stond bij de nieuwe terugkeer naar de universele vrijmetselarij Les Disciples de Salomon mee aan de wieg van de oprichting van de Reguliere Grootloge van België op 15 juni 1979. Op de lijst van aangesloten werkplaatsen, draagt de werkplaats het nummer twee, na de Franstalige loge l’Union uit Brussel. Ondertussen vermeldt het tableau van de RGLB al 58 loges, vele mee opgericht door Les Disciples de Salomon. Een is de Wijngaerdenranck, in principe een Aarschotse loges, maar ook actief in de Minckelerstaat. Die maçonniek turbulente jaren veroorzaakten een schokgolf in de hele Belgische vrijmetselarij , waarbij al dan niet een opperwezen of al dan niet de aanwezigheid van vrouwen in de tempel een rol speelden. Ook in Leuven werden andere obediënties actief. Onder het Grootoosten werd in 1978 de werkplaats Open Raam opgericht, en een jaar eerder kwam hier ook de gemengde koepel Le Droit Humain toe en noemde haar loge Daidalos. Zoals in Leuven en elders werd ook het verenigingsleven in Tienen getekend door de afscheidingen en spanningen, eerst tussen het Grootoosten en de Grootloge, en daarna tussen de Grootloge en de Reguliere Grootloge, ook al bleven velen elkaar ontmoeten in een Broederkring. Daaruit groeide midden de jaren 80 de zin om in Leuven weer een nieuwe werkplaats onder de Grootloge op te richten en zo ontstond Andreas Vesalius. Ook de onafhankelijke groep Lithos heeft hier een werkplaats, Houtskool, en zijn er, naast activiteiten van La Nef d’or afhangend van Frankrijk, ook nog ateliers van zogenaamde side degrees of hogere graden die volgen op loges die in de gebruikelijke drie blauwe graden werken. Niet zozeer om aan te tonen hoe ironisch geschiedenis wel kan zijn maar wel om de cirkel te sluiten, besluit ik deze lezing met een scoop. Onder het meterschap van Leuven consacreerde de Reguliere Grootloge van België gisteren op de dag van Sint-Jan haar 59ste loge: Athéna, à l’Orient de Louvain-La-Neuve. He had shot himself in the head on 20 February 2005. Six months later, his ashes were fired, from a cannon, into the stratosphere, accompanied by fireworks in red, white, blue and green.

He loved explosions, his young widow said, but when he had cocked his gun, she put the receiver down, assuming the blocked writer had finally struck a key on his typewriter, for she still had hope. She missed the final shot. His son, in a room next door, didn’t react immediately either: he thought a book had fallen to the ground. The suicide note was less literary though: “No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.” Hunter S. Thomson was a larger than life binge writer and reporter who didn’t have a story until he was in it. He called his new type of journalism: Gonzo. Inspired by Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, the juvenile delinquent from Kentucky quickly became a cult figure in Aspen, Colorado, where he’d even run for sheriff. Owl farm at Woody Creek was the personal lighthouse he always returned to from his many travels, a literary saloon with a shooting range. Fifteen books later, the icon of the sixties and seventies had become a jester in the retreat of Hollywood, a hero in the center of show business, sports and politics, having lost for himself all belief in the counter-culture that celebrated him. Drug and alcohol crazed Dr. Gonzo and his alter ego Raul Duke, eventually got in the way of Hunter’s own myth. Between the missed deadlines for the greatest magazines of his time, blasting away his weapons and making outraged phone calls and getting impossibly high or extremely wasted, the moral outlaw, the acclaimed beacon of dissent, got bored and just didn’t have fun anymore. He had been planning his burial for decades. Ultimately his Hollywood friend, Johnny Depp, fulfilled his last wish and funded the ceremony. From ashes to ashes, from dust to stardust: in a few colourful moments, Hunter became part of the cosmos. Hunter S. Thomson was named after an alleged forefather of his mother, the eighteen century Scottish physician and anatomist John Hunter. S. Thomson was a doctor too, not in medicine but in divinity; he had bought his title from the Universal Life Church, “just because he could”. 4/11/2017 0 Comments Pastiche Portraitnow in : "In Search of Andreas Vesalius - The Quest for His Grave, Lost and Not Yet Found", 14/02/2018.

now in : "In Search of Andreas Vesalius - The Quest for His Grave, Lost and Not Yet Found", 14/02/2018.

now in : "In Search of Andreas Vesalius - The Quest for His Grave, Lost and Not Yet Found", 14/02/2018.

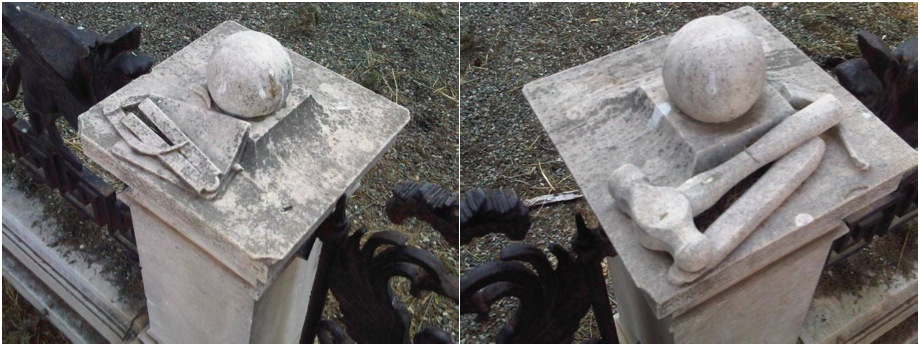

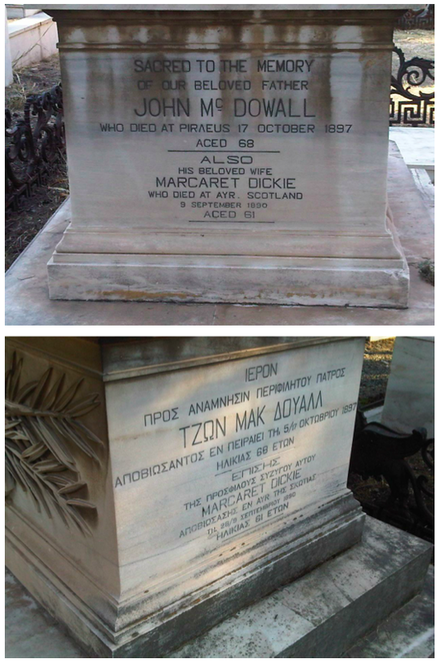

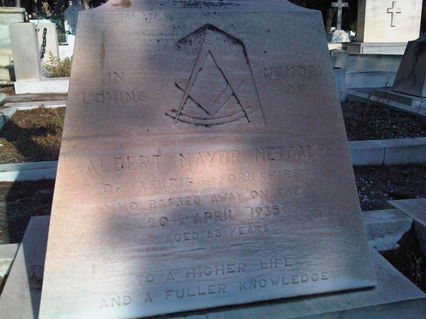

11/26/2016 0 Comments Eternal Masons RevisitedIn my stack of dead letters from Greece, only a few are in English. (A dead letter is a letter that cannot be delivered to the address written on it and cannot be returned to the person who sent it.) In the Greek Masonic Bulletin Pythagoras, issue 9 of 2002, I discover a fascinating article under the title: Eternal Masons. The accidental discovery of a grave with masonic symbols inspired the author to search for more tombs of Greek freemasons who “wished to declare their masonic identity through eternity from their grave”, and "who beyond death are still recognized by their Brethren as a mason". On the English cemetery of the Ionian island of Cephalonia, he finds the Square and Compasses engraved on a vertical tombstone with a semi circular frontispiece: “Sacred to the Memory of John Powers Late Drum Major 80 Regiment Died 2nd October 1830 Aged 36 years”. The author quotes the poem that follows and adds that: “as a token of respect this stone was erected by his comrade Sergeants (...) probably members of the same lodge”. My accidental discovery of a similar tombstone of a soldier/musician/mason at the English Cemetery of Zakynthos, from the same era, inspired me to revisit his Eternal Masons and search for some more. He only found “one Greek who disregarded the intolerance and obscurantism of his time”, I discovered a few more, not surprisingly, mainly on the Ionian Islands. This is not an inventory, neither a travel story, told chronologically or geographically; what follows is just a tale of some tombs of Greek freemasons expressing a bond between what has been and what is still to come. Within the walls of the municipal cemetery of the port city of Piraeus, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission takes care of a separate British Naval and Consular Cemetery: twenty three graves from the First World War. The small war cemetery lies at the end of the path to left from the Central Church of the Resurrection (Anastassis). The commission, so I read on their website, also takes care of twelve graves of marines who didn’t die in the war, elsewhere in this Third Cemetery. Maybe the memorial of John Mc Dowell who died in Piraeus on 17 October 1897, sixty eight years old, is one of them. Does the image of the anchor on his grave mean that he worked for the Navy? In freemasonry, the anchor is also depicted on one of the presentations of symbols, joining the Christian symbol for hope. Does the anchor rest on the branch of a palm or an acacia? As the author of my guiding article concludes: this is definitely an exceptional Masonic monument, “perhaps unique of its kind in Europe”. It doesn’t stand the comparison with the mausoleum of Eugene Goblet d’Alviella in Court-Saint-Etienne in Belgium, but in Greece it surely doesn’t have its equal: in its context it is as explicit, as courageous and as rich. The plot is enclosed by a cast iron rail of sixty centimeters height, standing on a stone base. On a ribbon of the repetitive Greek meander design, between several marble columns, two griffins are separated by thorns. The gate to the enclosure bears two sphinxes, looking at each other, holding blossoming thorns; on top of them an owl spreads his wings. The plot is divided in two: on the neighbouring monument to the right and on the two graves at the foot of this monument no Masonic symbols occur. We are acquainted with the mythological griffins with their heads and wings of an eagle and their feline body. They decorate many balconies of neo-classical buildings in Athens: from 15 Kanari Street and the Museum of Cycladic Art in Kolonaki over the Parnassos Literary Society to commercial buildings in Plaka: Quick Pitta, John Papanicolaou Furs, some ramshackle edifices in Athina Street. And on the residence of Heinrich Schliemann, the 19th century archeologist; today his mansion houses the Numismatic Museum and still hosts griffins and even sphinxes. If these sphinxes, half women half lion in its Greek tradition, from Delphi to the rooftop of Academia, often represent spirits who dare passersby to elaborate on the meaning of life, they indeed fit better on the gate to a grave than on the windows of an urban mansion. But why elaborate on the allegory and speculate if it, in its nineteenth century neo-classical version or in its earlier Greek representation, point in the direction of freemasonry, more obvious and recognisable on this tomb are the tools, casually placed upon the columns, on both side of the gate, as on an altar, accompanied by what appear being an earth globe and a star globe. What a pity sculptures on the other columns have disappeared. On one of them, only the feet of a bird, an owl perhaps, have survived vandalism. The monument itself is a temple resting on a base probably of Pendelicon marble, with in front the sign of the anchor, on the left the identity of the grave in English and the translation of the information in Greek on the right side. The temple is carried by four Doric columns, two in the front and two in the back. The bust of the deceased stands on a round column carrying proudly the Square and Compasses, in the second degree. He wears a medal: profane or masonic? On his cap the ribbon of meanders is depicted. First Cemetery of Athens No masonic imagery appears on the grave of Heinrich Schliemann, according to many a freemason indeed. On the contrary, the memorial, megalomania in stone, looks down on all who enter the cemetery, high from above, to the left just behind the entrance. I can only honour him with the photo of a simple red rose left by an anonymous admirer. The contrast with the stone commemorating one of Greece’s sons cannot be bigger: Emmanuel Xanthos, freemason and founding member of the secret liberty movement Filiki Eteria. Instead of an ostentatious mausoleum, I stand in front of a block of raw stone, bearing a simple cross, with a braided crown and a black ribbon placed against it; a metal plate refers to masons who fought for the independence, dating from 1930. On the backside of the base his name is repeated and several years are remembered: 1872 and 1905. Is this really his grave or is it a memorial? Has he been commemorated in these years? Have his remains been brought here? Or does he still rest on Patmos where he was born? Back to the Eternal Masons mentioned in the Pythagoras Bulletin. Within the fence of the Protestant Cemetery, still in the First Cemetery of Athens, against the outer wall of the main cemetery, lie the graves of two masons, openly claiming they were members of the order. Square and Compasses decorate their simple graves. On the first one, they mark the base of the cross in a large but simple bed of gravel; on the second one, our signs stand central on the simple slab. Albert Mayor Metcalfe of Askrigg Yorkshire died on 20 April 1935, sixty three years old. “To a higher life and a fuller knowledge”, says the stone. I don’t know if this is a standing expression; what I do recognise is the masonic sense of the thought. John Hadfield, born in Royton, England, on 25 August 1900, died in Athens on 20 September 1969: "God knew you were weary and he gave you rest". Square and Compasses are embedded in some kind of a bell. Both of them, John Hadfield and Albert Mayor, were former presiding masters, weren’t they? Another grave in the First Cemetery of Athens “lies behind the Church Of St. Lazarus, to the left, and belongs to the Galatis family”, so writes my guide. And further: “observing this partly underground monument, the marble cover to the reliquary has a small carving of a shield with the Square and Compasses”. I’ve been circling the Church of Lazarus as a Muslim the Ka’aba, until we, further on the path to the Protestant Cemetery, stumble upon the name of Galatis by accident. “Bro Galatis of Hesiodos Lodge is a hero of the National Resistance, member of the strike force of the resistance organisation P.E.A.N.A. (...) This is possibly the only Greek declaring his special identity from the grave”, so I read in my guide and add: discretely but unambiguously, inside, through the metal gate to the cellar, it stands clearly carved in marble. Flash back 1, December 2011, my first trip to Zakynthos: « The Italian occupier named the island the Flower of the East, as it also houses The Star of the East, the only lodge outside England resorting directly under the Grand Lodge of London. Zante has a thing with Freemasonry.” On the Ionian Islands of Corfu, Lefkada and Zakynthos/Zante the first lodges in Greece were established. Almost a year later, I discover on the Central Cemetery the grave of “Ioannis Zarakinis: worshipful Master of the English Lodge of Zakynthos”. Above Square and Compasses, only his name and Masonic function is noted, nothing more, no dates, no thoughts. On the foot stands a simple cross, in the large bed lie a fallen pot of flowers and grows a leaf. Only a foreigner would keep on looking for signs under the midday sun in a temperatures approaching 40°; there was a time when I wouldn’t hesitate defining more graves as Masonic, today I consider the “all seeing eyes”, “the obelisks” and “five pointed stars” as welcoming fata morgana’s where I can pause to drink refreshing water. Only one more tombstone carries unmistakably the signs. And so this well kept monument of Dionysios Pilarinos gets all the attention it deserves. He was a politician and a physician: “he devoted his life to his fellow men”. Below the tombstone has the illustration of a three armed chandelier and both sides have very prominently the Square and Compasses with the G. Driven by the article in Pythagoras, I visit the English cemetery of Zakynthos. Officially, the cemetery is closed because of “instability”, but after a few insisting returns, the caretaker of the neighboring garden shows me in. Here rest mainly British service men and a few non-orthodox gentlemen and even ladies who were not welcome in the local cemetery. I also found two English consuls, the one of the Peloponnesus, who died in 1689 and initiated the first of three English cemeteries on the Island, and the one of Cephalonia and Zakynthos who died in 1728. And then there is the gravestone of Fredrick Dedrick: “late Sergeant of the Band of the 11th Regiment of British Infantry. He is born in an unreadable city in Prussia in 1789 and died here on 23 October 1834. The stone was erected by his fellows of the band. On top of the monument, just underneath Sacred to the Memory of, are, in all its simplicity, the token of masons. The Story of Freemasonry on Zakynthos would not be complete without a visit to the church of Aghios Georgis ton Filikon or Saint John of the Friends. Flashback 2, December 2011, my first trip to Zakynthos: “The spot that once hit one of the biggest secrets of Greece lies in Psiloma, just above the city, after a sharp turn in Filikon street, coming from the street named after Capodistriou. On the north side of the church, in a small garden under an olive tree, the memorial for the Friendly Society attracts all the attention. To the south, under the clock tower, is a monumental grave; I cannot read who occupies the giant bird cage. Against the western wall, a remembrance of freemasons dates from 1925." The Synagogue, the Jewish cemetery and the war memorial of Chalkida are known worldwide. Today I come to check on one of the few Masonic graves of a Greek mason, already described in Pythagoras: “It is an ancient Greek type marble column, with a capital with thorns and a cross on the top. On the top part of the column is a laurel wreath in relief and in its center are the Square and Compasses. On the lower part is the inscription: (...); translated: “to the memory of our beloved parents Constantinos Fleggas and Adamantia Eliadou. Their Children”. Unfortunately, the beautiful capital has disappeared today: stolen or removed and kept safely elsewhere? Most masonic graves in Greece are of foreigners. In a last effort, I go to places where thousands and thousands of foreigners lie side by side. On the Phaleron Commonwealth Cemetery, on the busy Poseidon Avenue, opposite bars and yacht clubs in Vouliagmeni, almost 3000 soldiers of the other side try to find rest. The architecture is as straight, its tombstones identical, bearing almost all a cross, some a Star of David, a few the Fatiha. There is one Dutchman, 600 unknown, a memorial for the cremated, mainly Indian, and for the victims of the French-British campaign in the Crim.

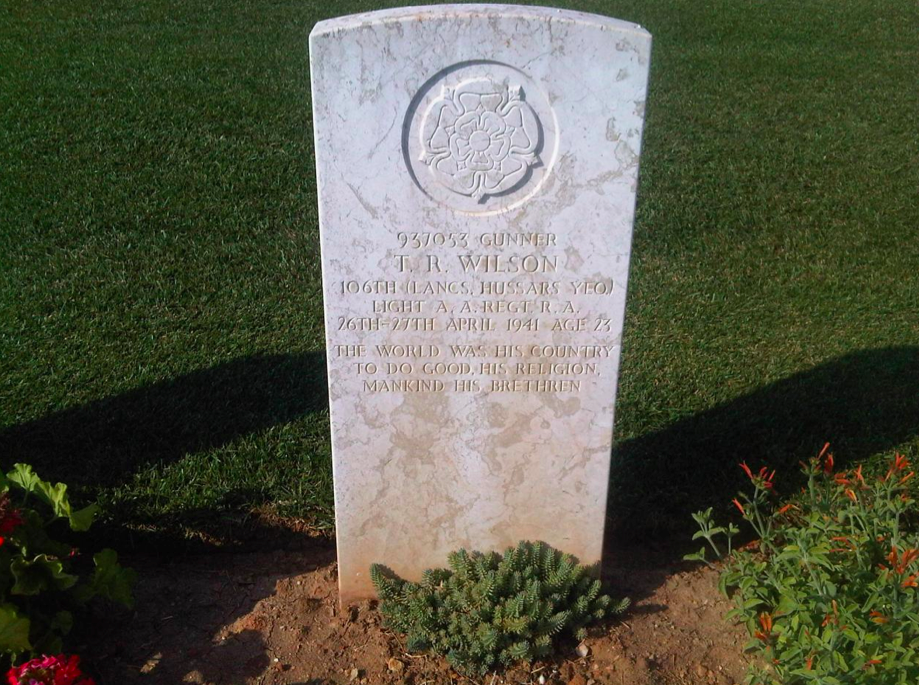

Between al this human waste, only the stone of twenty three year old T.R. Wilson catches my eye. This is one of the very few graves that do not bear a religious sign, neither an impressive coat of arms. This stone only carries a stylish flower, perhaps a Tudor Rose, and this subscription: "The World was his country to do good, his religion, mankind his brethren. The message sounds familiar to masons. Google confirms: “my country is the world and my religion is to do good”, is a well known quote of Thomas Paine from The Rights of Man, written in defense of the French Revolution in 1791-1792. Many other web sites quote the text more closely to the grave script of T.R. Wilson: “The world is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.” Apparently Paine was not always quoted correctly, even by the relatives of T. R. Wilson, who furthermore massacred the grammar. The notion of the brotherhood has probably been added by freemasons: relatives of Wilson? Or was Wilson a mason himself? We can only guess. Many doubt that even Thomas Paine was initiated. We only know he might have had some sympathy for the order. Didn’t he write: "An Essay on the Origin of Free-Masonry" (1803–1805)? Was Thomas Paine a mason or wasn’t he? Was T.R. Wilson a Brother of wasn’t he? In the end, does it matter? Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human rights clearly states: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood." now in : "In Search of Andreas Vesalius - The Quest for His Grave, Lost and Not Yet Found", 14/02/2018.

|

Posts may evolve in articles, or vice versa. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed